2001 is a film of three parts. It tells the not inconsiderable tale of our species' evolution. The first act is retrospective, showing us our ancestors, primitive apes in a stricken landscape, squabbling over water, before being confronted by a black slab - a monolith. This seems to trigger a change in the apes in which they 'discover' the concept of weaponry and use it to dominate a competing family of apes - the advent of human innovation. The plot then snaps to, presumably, 2001 where we follow a Dr. Haywood Floyd as he makes his way to an excavation site on the moon via a series of choreographed space-flights, ultimately resulting in our second encounter with the monolith. The plot then forwards again, a mere 18 months this time, to follow the events aboard the spacecraft 'Discovery' which is on a mission to Jupiter. Aboard the spacecraft are five astronauts - three in cryogenic sleep, two awake to manage the mission - and the HAL 9000 computer, an AI, considered a member of the crew, who governs the ship. HAL is meant to be infallible, and indeed all confidence in the mission is reliant upon his infallibility, so when he not only makes a mistake, but denies doing so, the two functioning astronauts, Dr. David Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole, secretly plot to deactivate him. HAL, attempting to preserve himself, sets Frank adrift in space without an air supply and murders the three astronauts in stasis whilst Dave is attempting to rescue Frank. Upon returning to the ship, Dave is denied entry by HAL, forcing him to risk his life manually breaching the hull. He then goes about deactivating HAL, node by node, as HAL pleads with him for his life. In doing so, a video message is activated revealing the true nature of the mission to Jupiter - to seek out alien life on the basis of a powerful signal emitted by the monolith. As Discovery nears Jupiter, the monolith appears again in outer space. Dave takes a space shuttle into/through the monolith, passing through a psychedelically visualised 'star-gate' before arriving in an otherworldly luxury apartment, in which he skips through stages of aging before being reborn as a celestial foetus (see fig.2.).

|

| Fig. 2 (1968) The celestial foetus |

The original score composed by Alex North was actually abandoned by Kubrick in favour of established classical and orchestral works, which had initially only been intended as guide pieces (LoBrutto, 1998:308)(Mcquiston, 2011:151). Kubrick didn't hesitate to design and alter segments of the film to fit the length of the classical and orchestral pieces he chose. He considered it essential in order to sustain select moods at distinct points of the narrative (Mcquiston, 2011:152).

Notably, Kubrick made use of several works by György Ligeti. In stark contrast to the majesty of the more classical works employed in the score, the more contemporary works of Ligeti are jarring, making heavy use of dissonance and ear-splitting crescendos.Their dissonance is used in the context of the air of the 'alien other' that surrounds the Monolith, repeatedly throughout the film to build tension, not necessarily with sinister intent, but more to signal an impending disruption of our, and the character's, expectations.

|

| Fig. 3 (1968) Opening Shot |

Similarly, the manner HAL murders the three astronauts in stasis is made truly chilling by both the speed the absolute silence (save for the machine hum of Discovery) in which it occurs. The film progresses at a sedate pace, uses minimal dialogue, and never presents a compelling human protagonist with whom the audience empathises. Instead it is the score that drives our emotional response and investment, and in divesting the murder scene of any emotional stimuli, the murders conveyed through nothing more than medical diagnostic devices, HAL is made truly monstrous to us, abhorrent, inhuman (Pezzotta, 2012:59).

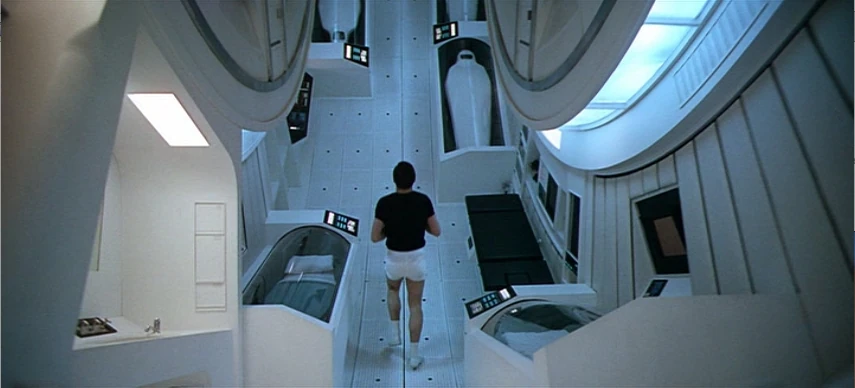

What is really happening though when the film lashes out with silence? It's impact does not derive solely from the absence of the score itself, but by what the score has built. 2001 is balletic throughout. Kubrick makes heavy uses of grand panning shots of the variety of spacecraft in the film as they pirouette through the void, elevating even landing sequences to sophisticated choreographed pieces, toying with graceful otherworldly motions only possible in 0G. The score doesn't merely reinforce this sense of dance, but imposes it upon you quite literally by making heavy use of The Blue Danube (1866) a waltz composed by Johann Strauss, and Aram Khachaturian's Gayane Ballet Suite (1939) (Pezzotta, 2012:53). Even within the interiors of the spacecraft the dance is present. "The gracefulness and weightlessness that are usually the attributes of dance also characterize the first scenes set inside the centrifuge of Discovery." "Their movements and those of the camera and the rotation of the centrifuge, accompanied by the Adagio from Aram Khatchaturian’s Gayaneh ballet suite, are like an acrobatic ballet in which the dancers challenge the weight of their bodies, in which the set slowly rotates to follow their choreography." (Pezzotta, 2012:54)(see fig.4.). As such, whenever silence is employed, the audience sits up and pays attention not merely because the score is absent, but because the dance has paused, it has well and truly ground to halt and there is no clear reason why yet - this in itself creates a narrative dissonance.

|

| Fig. 4 (1968) Interior of Discovery |

"The equatorial region of the pressure-sphere – the slice, as it were, from Capricorn to Cancer –

enclosed a slowly-rotating drum, thirty-five feet in diameter. As it made one revolution every ten

seconds, this carousel or centrifuge produced an artificial gravity equal to that of the Moon." (Clarke 1968: 113)

This principle of centrifugal force is a key consideration where application of REALISTIC artificial gravity is concerned. Space Operas have traditionally ignored, and continue to completely ignore the practical design issues space travel would actually pose - beyond the occasional Red-shirt being sucked out into space. Instead audiences are often treated to sci-fi in which spacecraft can just magically stick their occupants to the floor, totally violating our real-world understanding of the laws of physics. In this reviewer's opinion, films that actually design for the issues of space-travel are far more compelling as they do not require their audience to suspend their disbelief to such an extent - what they are being shown is not mere fantasy, it is legitimately viable. More recently, Neill Blomkamp's Elysium (2013) showcased the principal to stunning visual effect, and on a grand scale, with the toroidal design of the luxury space-station Elysium (see fig.BLAH) - every detail was considered as opposed to being simply conjured out of convenience. Elysium was surely inspired by 2001 in this regard.

|

| Fig. 5 (2013) Exterior of the Elysium space station |

The detailed considerations of the limitations of space-travel are the perfect complement to Kubrick's tendency toward single point perspective camera shots. Both the interior of the Space-station we encounter on Dr. Floyd's journey to the moon, and the main living space of the Discovery spacecraft conform to the centrifugal design, which combined with Kubrick's signature shot simulates an almost hyperreal experience as the environment curves both away from, and toward the audience on all sides. Other exemplars of the single point perspective twinned with the considerations of 0G are; the scene in which the space-airliner hostess turns and slowly walks herself up the cylindrical wall and onto what we would perceive to be the ceiling, before walking into the pilot's cabin; when Frank is shown spiraling helplessly into outer-space; and most interestingly, to simulate claustrophobia as the camera follows Dave in his space-suit as he exits Discovery (see fig.6.).

|

| Fig. 6 (1968) One point perspective shot of Dave exiting Discovery |

Kubrick's vision absolutely ignores the cinematic convention of the time. Minimal dialogue and his use of score to drive narrative and control the delivery of its visual experience was not some backpedaling homage to the silent film, but an insistence that film is not an extension of the stage play (Pezzotta, 2012:52,58-59). It's narrative challenges audience perceptions of monstrosity, humanity, gravity, even violence, and ultimately questions our purpose and place in the universe. It is a profoundly beautiful film whose age only shows in its wardrobe, and can only go unappreciated if its audience actively renders themselves incapable of intelligent thought.

Bibliography

Clarke, A. C. (1968). 2001: A Space Odyssey. London: Arrow Books.

LoBrutto, Vincent (1998). Stanley Kubrick. London: Faber and Faber.

McQuiston, Kate (2011) '"An effort to decide": More Research into Kubrick's Music Choices for 2001: A Space Odyssey' In: Journal of Film Music, The 3 (2) pp. 145-154

Pezzotta, Elisa (2012) 'The metaphor of dance in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange and Full Metal Jacket' In: Journal of Adaptation in Film & Performance 5 (1) pp.54-64

Rowe, Christopher (2013) 'The Romantic Model of "2001: A Space Odyssey"' In: Canadian Journal of Film Studies = Revue canadienne d'études cinematographiques 22 (2) pp.41-63

List of Illustrations

Figure 1. 2001: a space odyssey (1968) [Poster] At: http://www.panicposters.com/media/catalog/product/cache/1/image/f63dc5ec28f3175f8a7f615bd217eb71/m/s/msp0021_space_odyessy.jpg (Accessed on 23.10.16)

Figure 2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) [Film Still: The celestial foetus] At: http://trevorsviewonhollywood.weebly.com/uploads/3/8/7/1/38713721/1018060_orig.jpg

Figure 3. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) [Film Still: Opening Shot] At: https://filmshotfreezer.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/vlcsnap-2011-04-15-15h38m18s170.jpg (Accessed on 17.10.16)

Figure 4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) [Film Still: Interior of Discovery] At: http://vignette2.wikia.nocookie.net/2001/images/7/75/Discovery-interior.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20150214161632 (Accessed 23.10.16)

Figure 5. Elysium (2013) [Film Still: Exterior of the Elysium space station] At: https://www.wired.com/images_blogs/underwire/2013/08/F3_05_elysium.jpg (Accessed on 15.10.16)

Figure 6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) [Film Still: One point perspective shot of Dave exiting Discovery] At: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/4c/bb/0a/4cbb0a23b5b7cb71c1fac89b6afd1ed9.jpg (Accessed on 15.10.16)